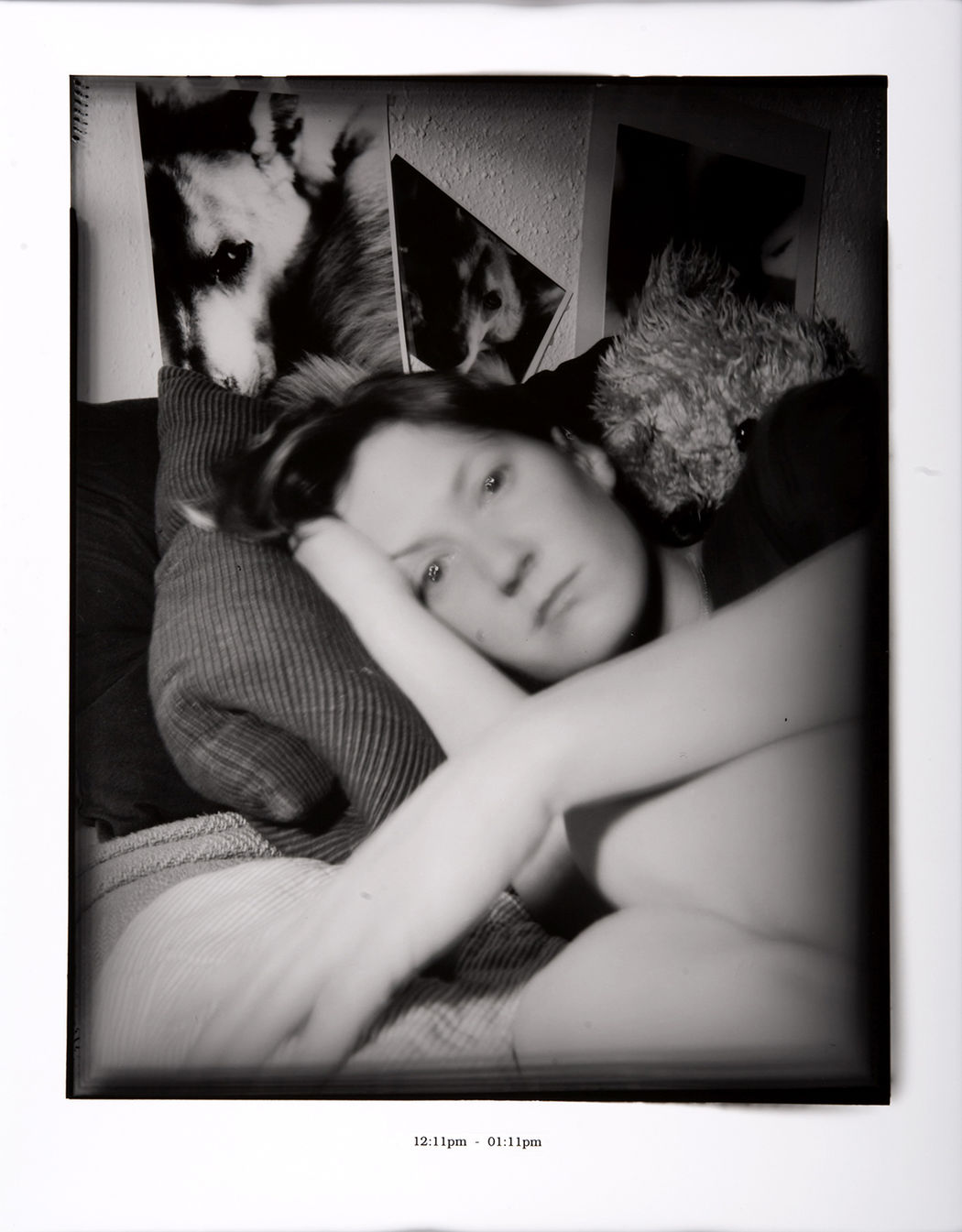

With, Ken Ohara’s 1998 series consists of one-hour-exposure portraits of strangers. Through the slow passage of exposure, the traditional expectations of portraiture—clarity, individuality, the decisive moment—dissolve into the stillness. While the outlines of a sitter's head and body soften and some details are lost, the portrait uniquely gains new dimensions. Around each sitter, lingering fragments of their world—a pillow, a wall, a shadow—offer quiet clues to who she/he is. Together, these portraits of a total of 123 form a collective meditation on time and presence, including the unseen artist behind the camera.

Ohara has always been deeply interested in time. His 1970s experiments, such as Diary/Self-Portraits (a pair of photographs taken per day, including one self-portrait) and 24 Hours (a self-portrait taken every minute for 24 hours), both look inward, tracing the shifting awareness of the self throughout the course of a day. But with feels like the inverse—an outward reflection on others. Here, he opens the camera for an hour and releases the photographer’s usual control over the moment. Normally, the photographer decides when to press the shutter, freezing a split second of intention and authorship. Ohara instead embraces uncertainty. The camera simply remains open, and whatever happens within that hour—boredom, stillness, daydream—is allowed to unfold on its own.

When I met the artist, he spoke often about Eastern philosophy, and I began to understand how deeply it informs his work. I think of with through the idea of wu wei—the Taoist notion of effortless action, or harmony with the natural flow of events. In these portraits, there is no attempt to impose will or control. Instead, Ohara practices a kind of photographic surrender. Time, light, and the subject’s own presence become the real collaborators. The result feels both spiritual and human: an image that holds traces of being, not through representation but through duration. The work invites us to reflect on the nature of existence itself—how our sense of identity is shaped by the passage of time, and how stillness can also be a form of movement.

I’m especially drawn to this image of a woman resting on a bed, surrounded by the softness of her own world. Even though her face is blurred, her gaze remains direct, almost confrontational. She looks both at us and beyond us, caught between presence and disappearance. I find myself wondering what she thought about during that hour—was she bored, contemplative, or simply hanging in that suspended time? The stuffed animal beside her and the photographs of dogs on the wall transform the frame into an intimate interior, filled with small, tender details. Even as her face and body seem to fade away, it feels personal and real, as if we’re being allowed to share her solitude.

To me, with is not only a portrait of its subjects but also of the artist’s quiet philosophy. It reveals how photography can be less about capturing and more about being with others, with time, with the world as it unfolds moment by moment.